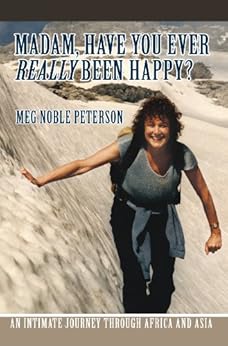

MADAM, HAVE YOU EVER REALLY BEEN HAPPY?: An Intimate Journey through Africa and Asia

She fearlessly leaves her life in New Jersey behind for a year as she embarks on the adventure she has waited her whole life to undertake.

Peterson’s intimate writing reveals her feelings about her recent divorce. Her personal writing gives the reader insight into the truth about traveling as a single woman approaching sixty.

Peterson refuses to view her age or her newly single status as hindrances during her journey. Instead, she takes every opportunity to engage in the world around her. In this except, Peterson explores the city of Varanasi with a helpful rickshaw guide.

Two days Until Kathmandu

An affable clerk booked me on a flight to Kathmandu, leaving in two days. No problem, I thought, as I stepped from the building and was caught up in a maelstrom of shouting, competing cab drivers. They leapt on me like a lion on a Thompson gazelle.

A stooped, bewhiskered old man offered me a fare of twenty rupees ($1.80) instead of the legal eighty-five for the fifteen-mile ride to town, and immediately became the object of loud denunciations. I entered his cab, judiciously rolling up the windows until we were clear of the airport.

The traffic came as no surprise. Trucks plastered with garish designs hogged the road and made passing perilous. HORN BLOW was printed in large letters on the back. The deep ruts combined with the lack of springs in the cab forced me to hold myself slightly above the seat, resting on my hands—a strain on my wrists, but better than putting my back out of alignment.

The scene was different from Agra. There was a frenetic activity everywhere you looked. In the makeshift markets along the way, I noticed several new varieties of green vegetables, giant pyramids of red peppers, and flat patties of dried cow dung neatly arranged inside large woven baskets.

Women bargained for the cheap local fuel, then carried the overflowing baskets away, expertly balanced on their head. Crowds of people bought dishes of steaming food. Mechanics fixed machines and bicycles with primitive tools. Bright-eyed youngsters stood in clusters, their arms around each other. And naked babies lay on slatted beds beside the road.

Weddings and Funerals

For the first time, I saw immense sleds loaded with sticks of wood to be used for funeral pyres on the banks of the Ganges. We passed a dead body wrapped in bright-colored shiny cloth—signifying a man—layered over the basic white. It was tied to a woven stretcher and pulled by a horse.

A young man in somber robes, head-shaven, walked alongside leading the horse. We passed slowly enough for me to get a good look at the man. I didn’t know that I would witness the cremation of that very body later in the afternoon.

Donkeys with hobbles joined the usual assortment of cows and bulls that snarled traffic. “The cow, Madam, is a symbolic mother, and is determined holy by the priest, who then makes a cut in her ear and throws the piece into the Ganges.” This was my driver’s explanation for the lofty position of these animals. It was the first time I’d heard that particular story.

We passed several decorated halls. “This is the season for weddings,” he said, “It is very expensive… a good reason to have boys.” Music blared at ear-splitting level. Golden yellow tinsel and shimmery paper streamers of electric blue and red hung down at the entrance, forming a door. Round bulbs all aglow had been hung wherever a hook or a pole could be found.

Just before we reached town the driver pointed out the house of the famed sitarist Ravi Shankar. The old fellow regaled me with many such tidbits, hoping I’d hire him as a tour guide.

I explained that I preferred to see the city on foot or in a bicycle rickshaw. But I let him know how grateful I was for finding me a hotel, where I booked a deluxe room for 110 rupees ($9.50) a night.

The proprietor of The Hotel India was handsome, gray-complected, with full lips, black mustache, impeccable clothes, and a distinctly aloof manner. This was a relief compared to most of the men I’d encountered behind hotel desks.

At first I was intimidated by his brusqueness until he flashed a smile that could have melted a glacier. It wasn’t until the next evening that I got a glimpse of why he was so controlled.

An open marble stairway led to my ample third-floor room. Like so many middle-class Indian hotels it had the look of tired elegance as if nobody had bothered to put on the finishing touches.

Crisp marble moldings around a beautiful stone floor contrasted with unfinished plastering and holes where a picture had once hung. Faded velvet curtains tried without success to hide cracks in the wall. Mothballs filled the drains in the bathroom, just like the Hotel Bissau in Jaipur.

I opened the French doors and walked onto the balcony, which looked over an expanse of walled-in lawn with an old mansion at the far end. A sign read: YMCA Educational Center. Outside the gate longhaired pigs roamed free, mixing with the bicycle rickshaws that hung around a small unpaved parking area. I liked the scene.

Past Lives in the Holy City

After washing up I decided to take a look around town. Ten drivers swarmed around me at the gate. Shouting. Gesticulating. As I was trying to extricate myself, I caught sight of a lone man on the periphery, a homely soul with protruding teeth and an emaciated body. He was just standing there, staring at me. He wore a drab tunic partially covering a calf-length dhoti. Why was I drawn to him? Physically, he was the ugliest man I’d ever seen.

“Dear lady,” he said, moving toward me. “Do not think me bold, but I know we have met in another life. We are not strangers….”

The oldest line in the book. But I stood there, intrigued by someone who wasn’t even interested in bargaining.

He took my hands into his. I didn’t pull away, enjoying the feel of his warm skin. He looked into my eyes steadily. There wasn’t a hint of insincerity. And no mention of happiness or pleasure.

“I am Shanker,” he said, keeping his eyes fixed on mine. “Do you wish to see our holy city? I can take you wherever you want to go. You pay me whatever you wish. It will be my privilege.”

“I want to see the Ganges. I want to see a cremation ceremony,” I said, like a child asking permission. Silently, he retrieved his decrepit rickshaw with its frayed blacktop hanging at half-mast and motioned for me to step in.

I sat back, drinking in this holiest of Hindu cities. Varanasi defined antiquity. It had survived three thousand years of history — Muslim invasions, the wrath of rival kingdoms, daily pilgrimages of the faithful. And the signs were everywhere.

Even the sacred cows were more visible. I had to laugh at the way they stood dumbly in the middle of town, straddling the cement center strips, blinking and chewing. One enormous brown and white bull caught my eye. He looked like an oversized statue, quite a contrast from the usual all-white or all-black Brahman with its irregular hump and massive shoulders.

As we rode toward the river I was struck, one again, by how acutely conscious I was of my surroundings. My radar was operating at all times. I wondered what I’d write if I drank in the atmosphere at home with the same intensity, the same critical eye. I might learn a lot about what’s right under my nose.

The Risks of the Rickshaw Ride

Shanker kept up a steady stream of conversation. “I’m from Nepal, and I haven’t met any real friends since I came to India. They are not as friendly as the Nepalese.” He paused before continuing. “I am also a holy man. You can tell by my hair.”

He freed a cascade of thick knotted hair, which he kept wrapped in a plaid, coarsely woven scarf, the long end becoming a banner in the wind as he pedaled. When he tried to secure the black mass with one hand, the bike swerved. I gasped.

He turned around to reassure me. “Have no fear my friend. I have never had an accident in seventeen years. I am now thirty-two and …” He narrowly missed a curb, a couple of animals, and a neighboring vehicle.

The route to the Ganges was rife with Shanker’s close calls. I clutched the worn seat of the rickshaw. Whenever I admonished him to be careful he’d turn halfway around to tell me he’d never had an accident. And swerve. I finally kept my mouth shut. After all, it wasn’t as bad as the motorcycle in Pune.

Buy This Book From Amazon Madam, Have You Ever Really Been Happy?: An Intimate Journey through Africa and Asia

Meg Noble Peterson, a freelance writer and world traveler based in Maplewood, New Jersey, has spent most of her professional life in the field of music education. She’s written and arranged thirty-eight books for the Autoharp and classroom instruments, traveling extensively to give lectures and workshops. She also co-authored a play that was produced in Deerfield, MA and has had her essays published in the New York Times, Newsday, and The Christian Science Monitor.

- Greece Getaway: Camping Hacks for Your Next Getaway - April 25, 2024

- Products and Clothing You Might Enjoy - April 25, 2024

- Saudi Arabia Might Be Your Next Getaway Spot - April 23, 2024